A bittersweet evening under the stars

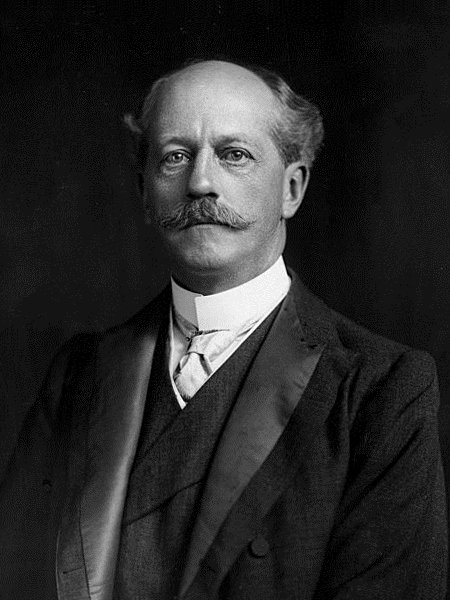

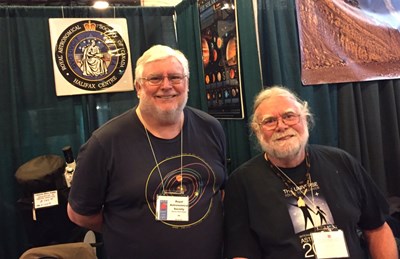

/Dave Lane is seen at Burke-gaffney Observatory at Saint mary’s University in April 2022. It was his last day at SMU where he worked as system administrator in the astronomy and physics department for over 30 years. He died in march 2024. - photo by tiffany fields

A first-quarter Moon, slightly hazed by wildfire smoke from afar, hangs conveniently low in the sky over Portland Hills on this spring evening.

As usual when there’s a “good” Moon out there, I’m on the balcony with a telescope and camera. We have a nice view of the southern horizon, which comes in handy at this time of year when the summer constellations rise into view.

I do have to contend with the light pollution that increasingly blights our night sky. The plaza next door is a particular challenge as it comes equipped with an array of security lights that would fit right in on the East German border when the wall still existed.

As a result, I’ve erected my own wall of artificial trees in the corner of the balcony. If I adjust my viewing chair appropriately, I can block most of the glare and enjoy the stars bright enough to penetrate the suburban sky glow.

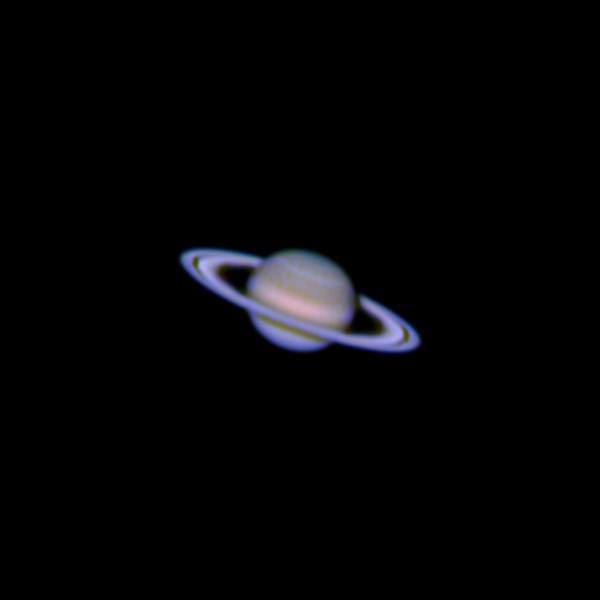

Much of astronomical observing has been limited to my “balcony sessions” in recent years as the result of ill health. So I’ve been doing a lot of lunar and planetary observing, although a newly purchased light pollution filter provides decent views of the bright deep sky objects such as the Lagoon and Orion nebulae.

My go-to scope these evenings is also a new purchase, at least new to me. It’s the definition of a bittersweet experience. The sweet: The TeleVue Pronto is a lovely scope. The bitter: It belonged to Dave Lane.

this pronto refractor telescope, which now stands celestial watch on my balcony, belonged to the late dave lane. - john mcphee

Dave, who died in March 2024, was a dedicated member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Beginning in the 1980s, he served in many roles, including national and local president, despite a busy work schedule as system administrator in the astronomy and physics department at Saint Mary’s University.

He automated SMU’s Burke-Gaffney Observatory so it could be used remotely from around the world, and he created Earth Centered Universe, a planetarium and telescope-control program that allows institutes the ability to operate their own educational astronomy platforms.

On top of all that and more (his resume would fill pages), Dave was instrumental in the design and construction of the Halifax Centre’s St. Croix Observatory, which opened for members’ use in 1997.

Among several endowment and legacy funds in Dave’s memory, partly supported by an auction last year of his astronomical equipment, his wife Michelle has created the St.Croix Observatory Property Endowment (SCOPE) Fund. There are $10,000 worth of matching funds available thanks to Michelle and Tony Schellinck.

You can find details on how to support this project on the Halifax RASC website.

As I put Dave’s scope on the tripod, I try to put the bitter aside. He was only 60 when he died from an aggressive brain cancer. In a just universe, Dave would be still using this scope.

But as a scientist he’d likely agree with one of my favourite writers, Iain M. Banks, who also died too young of cancer.

“The universe does not have our own best interests at heart, and to assume for a moment that it does, ever did or ever might is to make the most calamitous and hubristic of mistakes.”

I point the Pronto toward the first-quarter Moon. There’s an interesting terminator region to explore and the clear sky may not last that long.