Planets in focus: Secrets of an astrophographer

/Astrophotographer Art Cole stands next to his Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope at his Hammonds Plains home. (JOHN McPHEE)

When Art Cole started out in astronomy, he used a 20mm plastic refractor telescope to explore the skies.

“It was basically garbage but you could look at the moon with it and that’s pretty cool if you’re a kid,” Cole told me during a chat at his home in Hammonds Plains.

Several decades later, he’s still captivated by the moon, as well as the planets and deep sky objects such as nebulae and galaxies.

Of course, the equipment he uses has moved up several notches on the cool scale since his observing days as a child in Lower Sackville. Cole’s setup includes an eight-inch Celestron Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, an 80mm Orion refractor, two DSLRs (Canon 7d Mark II and Canon T3i) and an array of photo-processing software programs.

As the cameras and processing wizardry indicate, Cole’s specialty is astrophotography, which is why I ended up in his living room sipping tea and munching cookies under the watchful eye of the family dog Romeo.

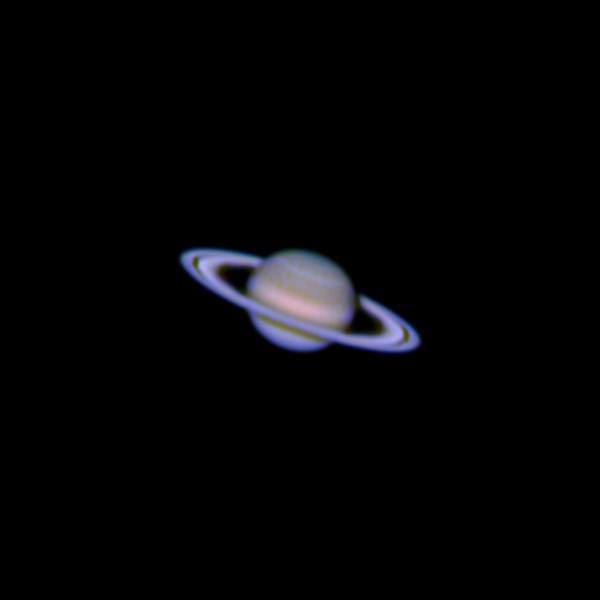

As a fellow member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, I’ve come to admire his work on planets such as Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, as well as deep sky targets such as the Orion Nebula and the Andromeda Galaxy. (Check out his Flickr page here).

Cole and other RASC astrophotographers such as Blair MacDonald and Jeff Donaldson produce amazing celestial portraits full of detail and colour.

I wanted to talk about Cole’s planetary photography techniques in particular because Mars (in the constellation Scorpius) and Saturn (in Ophiuchus) are rising into view in the evening southeast.

While Saturn and its famous ring system is a perennial favourite of astrophotographers, Mars’ disc is often too small to capture details of polar ice caps and vast lava plains. But Mars is closer to Earth than it’s been for 13 years so many planetary specialists are turning their camera-laden telescopes toward the Red Planet this time around.

So how does Cole get those sharp, detail-filled planetary shots? The short explanation is, don’t take photos, take video. And be prepared to spend a lot of time with those photo-processing programs.

Cole explains.

“If you’re looking through a telescope at an object, they’re blurry and all of a sudden, boom, you can see the Great Red Spot (on Jupiter). Or if you’re looking at Mars, boom, you can see the polar ice cap and other features and all of a sudden it disappears again.”

That inconsistency is caused by atmospheric turbulence. When the atmosphere is calmer, that’s known as a night of good "seeing."

“The idea behind video astrophotography is, you’re capturing an incredible amount of frames. ... I usually capture about 30 frames per second with my gear. ... Most of those frames are going to be in moments of poor seeing when the planet’s blurry and you’ll never get any detail. Whereas a certain percentage of them will be moments of good seeing. The planetary imaging details will be nice and sharp.”

That’s where the processing software comes in.

He recommends a popular, and free, software program called Registax. He also uses PIPP, which stands for Planetary Image Pre Processor.

“It goes through your video, every single frame. It determines whether or not they’re blurry or they’re sharp. And it will re-order them from best to worst. And you can say, I want to keep the best 10 per cent or 25 per cent or whatever.

“If you have really, really good seeing, you might keep 80 per cent of the frames. With poor seeing, you might keep 10 per cent. But usually I keep around 25 per cent, that’s OK. In the end, you wind up with a much shorter video with much better frames in it.”

But wait, there’s more — processing, that is.

Because it’s video and the exposures are short, they tend to be very grainy: there’s a lot of “noise” from the camera. As well, the image of the planet will jump around in the video because the wind slightly nudged your telescope or your tracking drifted a bit.

Registax and PIPP can be used to align the frames so the planet remains in the same spot and reduce the noise.

For the finishing touches, such as bringing out the details in the image, you guessed it. More processing! Cole favours Images Plus, although other programs such as Photoshop can be used.

Cole offered a few other tips to budding astrophotographers:

Use the gear you have (if you have it.) Don't spend money on expensive new gear until you've mastered what you have.

Learn the ins and outs of your processing software. You can work miracles out of digital data if you understand what digital processing tools you have at your disposal.

Be creative in your processing techniques and try out lots of new ideas.

Learn from other people to find out how they create their images. The Internet can be helpful too, but beware — much of the information in online discussion forms can be misleading or just plain wrong.

Cole’s grasp of the technical aspects of astrophotography comes naturally. He’s an engineer for JASCO Applied Sciences, an underwater acoustics company that measures the exact amount and impact of sound for environmental reviews of offshore and other projects.

He’s also worked as a systems engineer at MDA Corporation, a communications company that specializes in satellite technology and robotics. MDA’s projects have included the Canadarm on the International Space Station and the Earth observation satellites RADARSAT-1 and 2.

“I’ve always been interested in all kinds of sciences — biology, physics, math, astronomy, the whole thing,” Cole said. “I used to read encyclopedias for fun when I was a kid!” (Courtesy of his mom, who bought an entire set from a door-to-door salesman.)

Not surprisingly, he’s put his engineering and design skills to good use as an astrophotographer. He designed his own bracket (see photo above) to attach his iPhone to his telescope, which in fact sparked his interest in astrophotography several years ago. He wrote an article for Sky and Telescope's February 2013 issue about the project, which in turn led to an invitation from Mount Wilson observatory near Los Angeles to experiment with the iPhone bracket on the venerable 60-inch telescope.

Besides possible upgrades in equipment (“there’s always the appeal of better cameras”), Cole doesn’t foresee any big changes in how he captures his celestial portraits.

When he started out in astrophotography, he figured he’d be able to image three deep-sky objects a night. Not so much.

“You might do three nights per object. At this rate, I’m never going to run out of stuff to take pictures of. I just really enjoy it.”