Let's play name that star

/the double-star star Zubenelgenubi is seen to the lower left of jupiter in august 2018. - john mcphee

About 10,000 years ago, skywatchers in the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia, were the first to put names to what they saw in the heavens.

And they came up with some great ones: Zubenelgenubi. Unukalhai. Rasalhague.

The stars that inspired these names were more than just pretty things to look at for the ancient Arabs. Since agriculture was crucial to the civilization in what's now Iraq, the stars that accompanied the changing seasons helped mark the best time to sow and to reap.

Many of the names they gave the stars have survived the ages. The star that gets my vote for best name, Zubenelgenubi (zoo-BEN-el-ja-NOO-bee), is found in the constellation Libra.

Zubenelgenubi

Zubenelgenubi, also known as alpha Librae, is a double-star system 77.2 light-years from Earth. Image via AAO/ STScI/ WikiSky

Zubenelgenubi forms the western corner of the triangle formed by Libra's brighter stars. To find this faint constellation, look between the bright stars Antares low in the south and Arcturus, higher and to the west.

If you've got sharp eyesight, and are away from city lights, you'll notice that Zubenelgenubi has a much fainter companion. The pair, which is likely a true double-star related in space about 77 light-years away, gets more interesting in binoculars or a wide-field telescope. You can see a striking contrast between the blue main star and the whitish (some observers say it's yellow) companion.

Another celestial tongue-twister, Unukulhai (oo-NOOK-ul-eye), can be seen in small, dim constellation above and to the east of Libra. Unukalhai is the only star that stands out in Serpens Caput, the Neck of the Snake. It's also a multiple-star system but its two other companions aren't visible.

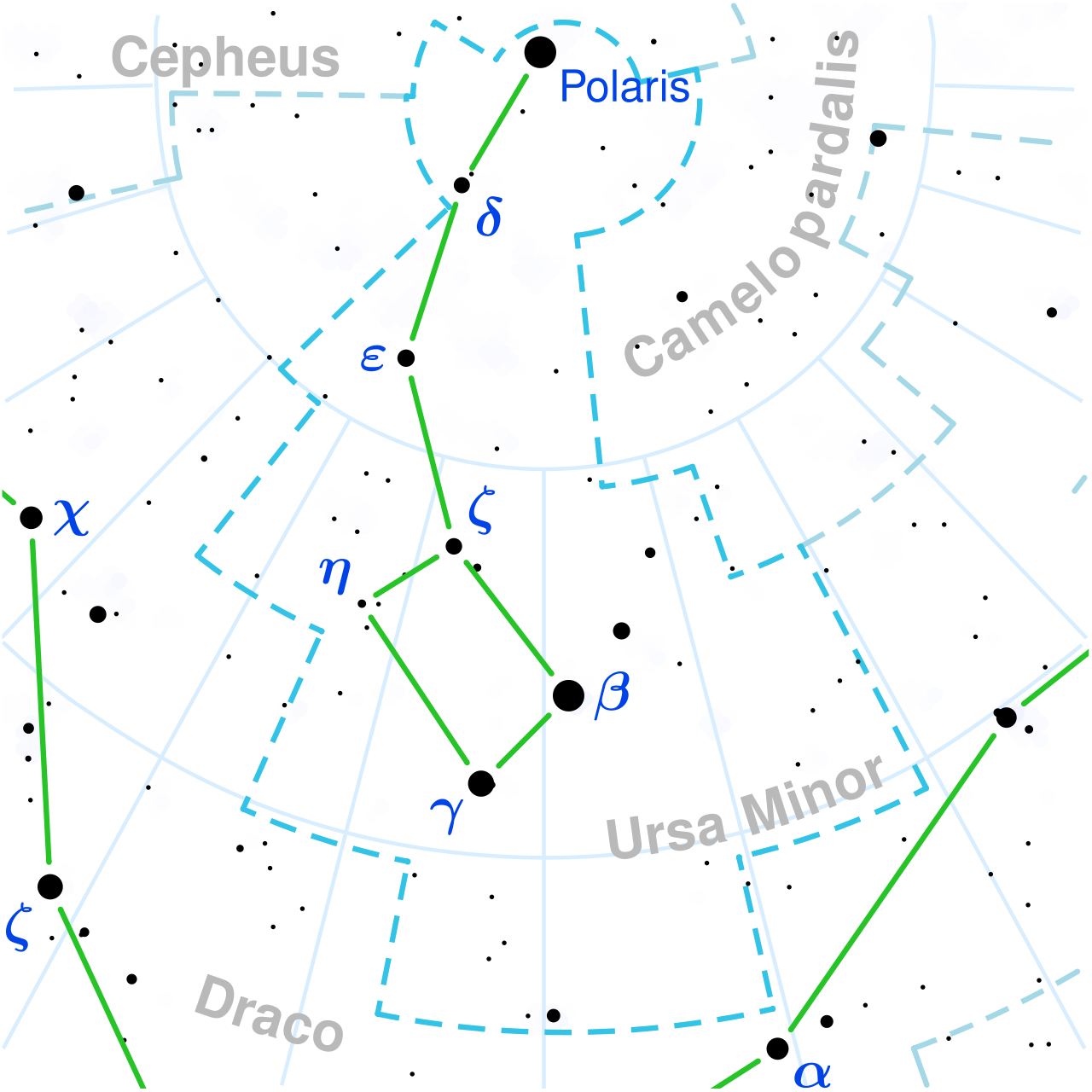

Stars revolve around Polaris, the north star, in this long exposure. - john mcphee

Not just any star

Look to the opposite side of the sky to find another star whose name dates back through the millennia. It's easier one to pronounce, Kochab (KO-cab), which may come from al-kawkab, Arabic for "the star." According to Wikipedia, this singular name may refer to the fact Kochab was close to the northern pole at about 1,100 B.C.

For us, of course, another star has that distinction. All stars in the sky appear to revolve around Polaris, the North Star, because now it's located directly above the Earth's northern axis.

You can easily track this motion by watching the Little Dipper (Ursa Minor) through the night, as Kochab and the other Dipper stars swing around steadfast Polaris.

The Dipper's appearance can be predicted from month to month as well. On June evenings at about 11 p.m., Kochab can be seen at the 12 o'clock position, if Polaris were the centre of the clock.

You'll probably notice Kochab before you see Polaris, even though Kochab is slightly dimmer. It has a distinctive orange hue that really jumps out in binoculars or a scope. Kochab is an impressive star by any measure - it's 500 times brighter and 50 times the size of our sun.

Ancient connections

The first peoples of Canada used this group of stars to guide their travels under the northern skies. The Plains Cree called Polaris the standing-still star, Ekakatchet Atchakos, or Keewatin.

“If a Cree traveller kept Keewatin on their right shoulder while moving over land at night, they knew they were travelling towards the west,” according to information on the University of Calgary’s observatory website.