Celestial summer visitor

/The comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) hangs over the community of gore, Nova scotia, on July 21, 2020. - john mcphee

Forty-eight years ago, I watched the day turn into night on a July afternoon.

I was seven years old for the solar eclipse of July 10, 1972. I knew the basics of what was going on - the moon was blocking the light of the sun. I remember chatting excitedly with my siblings as we crowded around a window in our home in Cape Breton. We watched from inside after hearing warnings about looking directly at the sun (It’s only safe during the brief moment of totality).

I felt unsettled and a little afraid as an eerie twilight descended on that summer day. But the eclipse sparked a lifelong curiousity about the moon, stars and planets.

That interest waxed and waned over the years until 1996, when another remarkable celestial event steered me back into the hobby. The comet Hyakutake put on an amazing show in March of that year as its long tail spread across the meridian.

comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) on july 21, 2020. The comet’s sweeping dust tail as well as a narrow blue ion tail are visible- john mcphee

I was living in Annapolis Royal at the time, where the skies were, and remain, mostly unspoiled by light pollution. We had an excellent view of Hyakutake.

Just a year afterward, a smaller but brighter comet, Hale-Bopp, was visible to the naked eye for a record 18 months. Other comets have come and gone in the intervening years but none have approached the spectacle of those two celestial visitors.

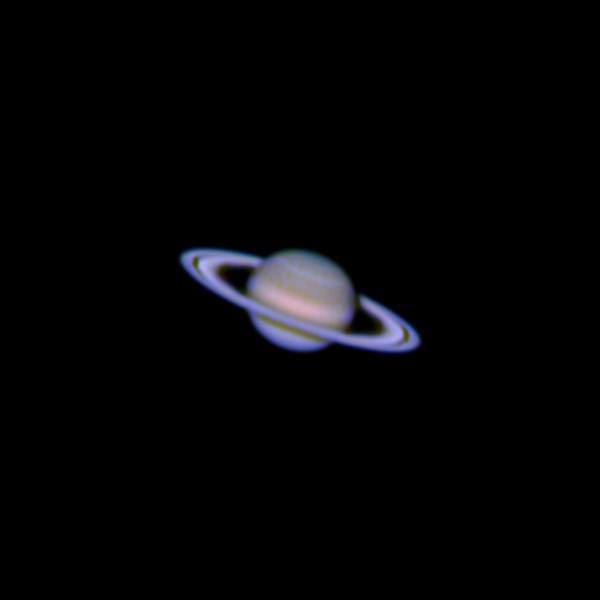

But over the past month, C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) has put on a pretty good show. This comet appeared in the northern hemisphere as a pre-dawn binocular object in early July. By the latter part of the month, it had moved into the evening sky in the northwest, when it became visible to the naked eye away from light pollution. NEOWISE reached its peak brightness when it came closest to the Earth - about 103 million kilometres - on July 22/23.

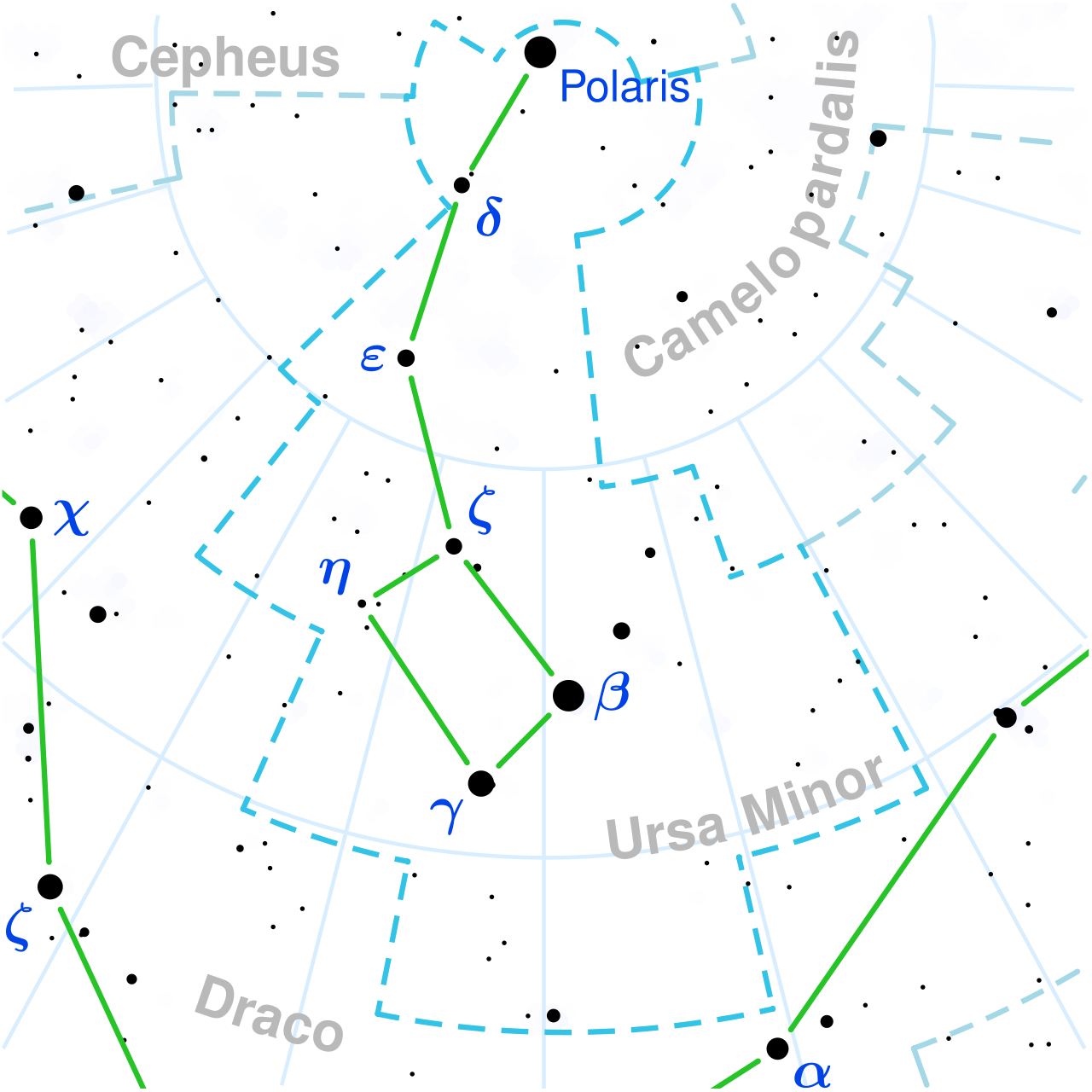

I had my best moment with the comet the night before, along with dozens of other people who had gathered on Courthouse Monument Hill in Gore, Hants County. That vantage point allows a sweeping view of the northwest, where NEOWISE’s faint spray of light was visible under the Big Dipper once darkness fell.

C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) hovers below the big dipper on july 21, 2020. The open cluster of stars on the left is the tiny constellation Coma Berenices. - john mcphee

It was a lovely sight in binoculars and also made for an interesting photo target with its narrow blue ion tail and sweeping white dust tail. Astrophotographers have captured amazing images of the comet’s fascinating structure.

Over the past few days, It’s dimmed considerably as it moves away from the sun. Who knows if humans will still be around to see it but NEOWISE will make a return visit in about 6,000 years.