The dark skies of Kejimkujik

/The trails of red-filtered flashlights are seen during dark sky weekend at kejimkujik. (john mcphee)

Check out any astronomical event and you’ll find two kinds of observers.

There are the extroverted types for whom the social aspects of the gathering are just as important as the celestial.

During an interview in the spring, fellow observer Art Cole told me he often sets up his camera/telescope rig to automatically take photos or video of a particular celestial object for hours. Then he makes the rounds to chat with fellow astronomers.

On the other end of the extrovert/introvert spectrum, there are people like, well, me. My routine at an astronomical gathering is exchanging a few pleasantries after arrival and finding a good spot to plant my ‘scope. For the rest of the evening, my eye is stuck to the eyepiece and you might hear an appreciative mumble once in a while when I get a good view of an object.

No, I’ll never be the life of the astronomical (or any other) party. But I try to come out of my shell each summer for Dark Sky Weekend at Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site in western Nova Scotia. I have offered my telescope and limited astronomical know-how several times at the event's public observing sessions.

It’s a great time. Hundreds of people converge in the evening at the Sky Circle in Jeremy’s Bay Campground for astronomical and native cultural presentations by RASC members and Parks Canada interpreters. Afterward people line up to peek through the telescopes set up around a large field surrounding the Sky Circle.

I particularly enjoy providing celestial views to enthusiastic younger observers, many of whom have never looked through a telescope.

Keji’s dark sky program is the result of a collaboration between Parks Canada and the Halifax Centre of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. The society, represented by members Quinn Smith and Dave Chapman, approached Parks Canada in 2009 about getting Keji designated as a dark sky preserve.

Parks Canada would have to implement light pollution controls at the park, offer astronomical programming and public outreach activities, and promote Keji as a stargazing destination.

A former civil servant, Chapman braced for a long haul of bureaucratic stonewalling.

“What happened to our surprise was ... we got invited down and it turned out the people at Keji were all for it,” Chapman said in an interview.

RASC members helped train park interpreters on such things as features of the night sky and astronomical equipment (the park bought a large Go-To telescope for use at the Sky Circle). And society members remain heavily involved, particularly on Dark Sky Weekend every August.

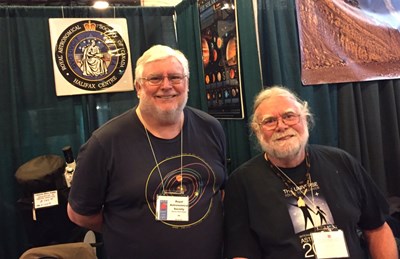

RASC members Dave Chapman and Quinn Smith spearheaded the creation of the Dark Sky Preserve at Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site.

Six years later, Chapman says he’s very pleased with how the program has evolved.

“I’m very impressed at how they’ve handled it. It wasn’t like, ‘OK thanks, we’ll take that and we’ll put it on a webpage.’ They’ve really embraced the whole idea of the preserve and how it adds to the park and they’ve incorporated it into their programming.”

RASC members Dave Chapman and Quinn Smith spearheaded the creation of the Dark Sky Preserve at Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site.

RASC members have tailored their own contributions to Dark Sky Weekend over the years. For example, they’ve reduced the number of daytime activities, which weren’t drawing a lot of people, in favour of “drop-in” events, Chapman said.

“We set up a station, a little tent (near the Tuck Shoppe at Jeremy’s Bay Campground) where we could sit under the shade and we basically have a drop-in where people could just come to us,” he said. “We’ll show them free handouts, talk to them about telescopes and do solar observing. That was really quite successful last year so we’re going to do that again this year.”

Chapman’s involvement with the dark sky project is but one of his many irons in the astronomical fire. He’s edited the internationally renowned Observer’s Handbook published by the RASC, he curates the www.astronomynovascotia.ca website and, along with Mi’kmaq cultural interpreter Cathy Jean LeBlanc, he created the Mi’kmaw Moons project.

Public outreach in astronomy hadn’t been a big interest for him until relatively recently. But Chapman has come to enjoy the one-to-one contact with people at events such as Dark Sky Weekend.

“It’s amazing how many people you meet who just have never — well, they may have looked at the sky but they don’t know what they’re looking at. So ... you point out the Milky Way, this is our galaxy, these are the stars, that one’s a double star, that one’s a planet — people love that stuff, they want to appreciate it.

“What I tell people all the time is, you don’t have to be a scientist or an astronomer to appreciate the sky. You can appreciate it for what it is, from wherever you’re coming from. You don’t have to understand the physics of it all. If you want to understand the physics, we can tell you that too, but if you just want to enjoy it, we can tell you what you’re looking at.”

Secret codes and nocturnal encounters

Look closely at the bottom of the photo for four green streaks created by a passing firefly in this long exposure of Scorpius. (JOHN McPHEE / Local Xpress)

Many a night I saw the Pleiads rising thro' the mellow shade,

Glitter like a swarm of fireflies tangled in a silver braid.

Alfred Tennyson

It’s a warm sultry summer night. The stars are twinkling, a light breeze teases the trees, a barred owl hoots in the distance.

Perfect for a little romance.

Actually, judging from the number of little lights flitting about the woods and lake shoreline where I’m observing the night sky, there’s lots of hooking up going on.

Yes, the fireflies have come out to play on this late June evening. Their mesmerizing now-you-see-them-now-you-don’t performance is keeping me entertained while my camera soaks up photons from the great beyond. The planets Mars and Saturn are passing by the constellation Scorpius low in the south so I’m shooting some long exposures to capture this celestial grouping for posterity.

Fireflies have been synonymous with summer for me since childhood. I was fascinated by these “lightning bugs” who seemed to be visitors from a magical fairy world.

Alas, the reality is less romantic. Fireflies aren’t actually even flies, they’re soft-bodied beetles. If you held one in your hand during the day, you’d see a bug with a dark backside and an orangish front.

And those ethereal lights are actually the result of a protein reacting with an enzyme. Nothing very magical there.

After my night among the celestial and insectoid lights, I called up Andrew Hebda, the curator of zoology at the Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History, for the scoop on these summer visitors.

There’s indeed a romantic aspect to the reason these insects light up the night. Well, romantic in a glowing beetle butt kind of way.

The light produced on the insect’s tail end is created by a fairly simple chemical reaction, Hebda explained.

“They have a photo-luminescent protein called luciferin. When it’s exposed to an enzyme called luciferase, which is released upon a given stimulus, it essentially causes the excitation of luciferin to a higher stage, and as it decays, then it releases light. It’s a very straightforward chemical decay process.”

Not so straightforward is exactly how the message “OK, turn my backdoor light on” is triggered in the beetle’s brain. “That’s the process they don’t understand clearly,” Hebda said.

But the goal of this photochemical wizardry is clear: Find a mate and fast. The males produce their signal in a particular pattern to tell females that they’re around, they’re available to mate, Hebda said.

Fireflies love a warm and calm summer evening. This is a stack of 29 30-second exposures taken on a country road in nova scotia. - John Mcphee

“Essentially the pattern is sort of like a Morse code, it’s very species-specific. You can use the analogy that one may be flashing an S and one may be flashing the letter P. Based on the pattern of flashes, the potential mate will recognize that and respond to that.”

Fireflies don’t have the best eyesight so the successful light signal must be close by, he said.

The females also use light patterns to respond to males or to attract them — both for sex or for a free lunch, it turns out. Some female fireflies mimic the light patterns of other species, lure the unsuspecting Romeo into their lair and gobble him up. Nice.

If there’s a happier ending to the love story, the female usually lays her eggs soon afterward. The mating and subsequent egg-laying usually takes place in sheltered wetlands and bays.

“You’re not going to find them in the middle of open, windy dry areas,” Hebda said. “They’re not aerodynamically designed to cope with strong winds so you tend to find them in wetland areas where you have some protection from wind ... They have to be near the appropriate habitat for both the eggs to be able to ripen and hatch and larvae to feed.”

There are about 2,000 species of fireflies across the world. The nine types found in Nova Scotia are true fireflies — some species that fall into the Lampyridae family don’t light up. Exactly how many fireflies flit around on a typical Nova Scotia summer night isn't known, Hebda said.

“I have a farm on Cobequid Bay and there are a couple of wetland areas there and it’s not unusual to see 40 or 50 (fireflies). Within that individual one hectare of wetland, we may have several hundred individuals because, of course, you’re only seeing the males. The females will either be up in the shrubbery or down in the ground. You tend not to see those ones.”

As a zoologist, Hebda is obviously interested in the creepy crawly set. “Anything that runs, flies, swims or crawls. If it’s dead, it stinks. If it doesn’t stink, we call it palentology.” (We’ve only met on the phone but it’s clear this scientist comes equipped with a tinder-dry sense of humour).

It’s fair to say most people don’t share his love of the insect world. Even those who enjoy the spectacle of fireflies at night would get out the broom if they spotted one of those beetles crawling across the floor in the daytime.

“I blame our parents completely for that,” said Hebda, perhaps only half-jokingly. “Of course, we’re supposed to keep things clean ... ensuring that you don’t have vermin and insects that are crawling around.”

When it comes to fireflies, “the other elements that some people may find repulsive are masked by that absolutely gorgeous and mysterious sight. We may know the chemical processes as to how it works but still it’s a mystical thing.”

I can only agree as I later look over my exposures from the Scorpius session. A few have been firefly photobombed with short, green streaks of light. Just beetles. But pretty magical ones just the same.